What is a concept book?

A concept book, as the name indicates, introduces a basic idea or a concept to the readers. Some classical subjects are

- Alphabet

- Shapes

- Colors

- Telling time

- Numbers & Counting

- Naming emotions

- Animals & toys

- Basic vocabulary (MY 100 FIRST WORDS, …)

These types of concept books mostly publish in board book format and their audience is very young-children—toddlers and pre-kindergarten children.

However, concept books are a perfect medium to speak about tough topics or less spoken/appreciated cultural topics. The target audience of this kind of concept books are elder children (4+) and these books are published as picture books, not board books. In this blog post, I studied some examples.

This blog post is about concept books that are very creative.

Concept books vs. high-concept books

High-concept books are stories with an overarching ‘What if?‘.

For example, “What if we could clone dinosaurs?” as in Jurassic Park. Another example of a high-concept book is NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR, which its high-concept idea is “What if we lived in a future of totalitarian government?”. In this blog post, I discussed high-concept picture books.

High-concept books are stories and have Narrative Structures. Concept books are NOT stories and don’t have Narrative Structure. I will discuss it later.

Writing Concept Books

Concept books are not stories. Thus, they are not constructed with a Narrative Structure (Beginning-Middle-End) Concept books are written with a Description Text Structure. And exactly, for this reason, drafting a concept book needs much extra care because while writing a story, we have the guidelines of the Narrative Structure. It is like riding on a highway with many signs and guardrails. Writing concept books is like walking in a forest. You can easily get lost. This is when the manuscript goes on and on and on with examples and lacks a clear discussion/conclusion. The manuscript can easily get swamped in rhyming words and becomes a purple purse.

When I was thinking about writing concept books, one question daunted me: How can I distinguish a wordy description from a description that sheds light on the concept? When is the description enough and when it isn’t?

To have a better understanding, I studied recent traditionally-published concept books which in my opinion are well-written. And here is the result.

Culture-themed concept books

For the culture-themed, I compare the four following picture books with one another:

- FRY BREAD: A NATIVE AMERICAN FAMILY STORY (2019) by Kevin Noble Maillard and Juana Martinez-Neal.

- A DUPATTA IS … (2023) by Marzieh Abbas and Anu Chouhan (available on Edelweiss)

- THE BIG BATH HOUSE (2021) by Kyo Maclear and Gracey Zhang

- BEE-BIM BOP! (2005) by Linda Sue Park and Ho Baek Lee

Books (1) and (2)

Another example:

- NAMASTE IS A GREETING (2022) by Suma Subramaniam and Sandhya Prabhat

- IT’S DIWALI! (2022) by Kabir Sehgal and Surishtha Sehgal

Books (3) and (4) are different. THE BIG BATH HOUSE begins with a little girl going to a traditional Japanese public bath, explains the steps, and ends when the visit to the bath is finished. Similarly, BEE-BIM BOP! starts with a girl going shopping with her mother and explains the ingredients and steps of cooking a traditional Korean food—Bee-Bim bop. When the food is ready to book finishes.

The concept of BEE-BIM BOP! is the only food. While the concept of FRY BREAD is food as an identical icon. So, only the first four spreads of FRY BREAD are about the ingredients and preparation. Then the book zooms out on the topic and looks at the cultural role of fry bread among Native Americans.

To me, the difference seems like when you want to record a film of a flower (just an example). You have two options: either you can zoom in on the flower (books (3) and (4)) or first zoom in at the flower and then zoom out and show the view of the valley (books (1) and (2)).

Going back to my question, let’s assume I want to write a concept book about a national celebration of my homeland—Iran. It seems logical that I have to organize my concept first. Is my concept the celebration itself? Or, is it the role of this celebration in the frame of Iranian culture? If former, I can write 7 or 8 spreads about the traditions. Yet, if later, I ought to shorten the tradition’s spread into 2 or 3. Otherwise, I consume (and waste) the reader’s attention on what is not that necessary in the concept I want to present.

More examples of this category:

- FESTIVAL OF COLORS (2018) by Surishtha Sehgal and Kabir Sehgal (Authors) and Vashti Harrison (Illustrator)

- BÁBO: A TALE OF ARMENIAN RUG-WASHING DAY (2023) by Astrid Kamalyan and Anait Semirdzhyan

Nature-themed concept books

(1) HELLO, PUDDLE! (2022) by Anita Sanchez and Luisa Uribe (read this on Edelwise)

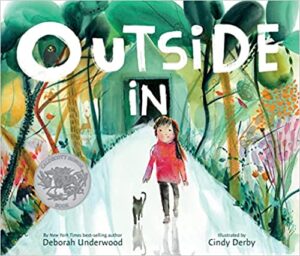

(2) OUTSIDE IN (2020) by Deborah Underwood and Cindy Derby

The focus of the book (1) is only on puddles and the life formed around them. The concept of the book (2) is totally different.

Emotion-themed concept books

Writing this category is the most challenging one, I assume. Because a writer can go on and on and on in describing a feeling and exhaust the reader’s attention. In stories, also, explaining emotions is the tricky part.