What is the narrative structure?

When someone wants to tell a story, how should she organize the story segments—characters, dialogue, conflict, scenes, etc? As far as we know, Aristotle, the Greek philosopher, is the first person who tried to answer this question. In his book, \textsl{Poetics}, he wrote:

Aristotle was the first one, but not the only one. About 2100 years after Aristotle, in 1863, Gustav Freytag, the German playwright and novelist, analyzed ancient Greek tragedies and Shakespeare’s works and published his study’s result in a book; Die Technik des Dramas. In 1894, Elias J. MacEwan translated Freytag’s book into English; Freytag’s Techniques of the Drama.

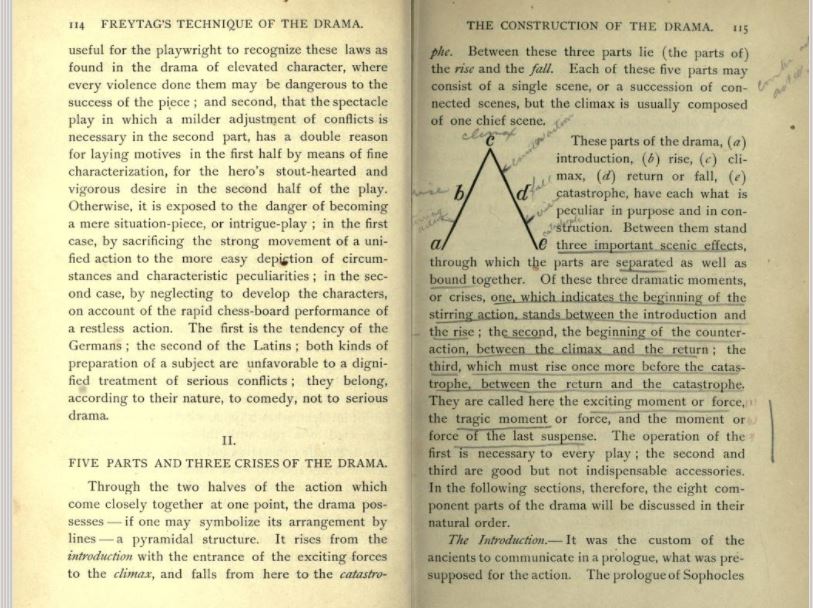

Freytag moved our understanding of storytelling forward by drawing a typical narrative form on paper.

Today, we call it Freytag’s pyramid and the term Narrative arc initiated from his idea.

The effort for understanding the structure(s) of stories kept playwrights and writers busy. In 1979, an American author, Syd Field,  published a book for screenwriting; Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting.

published a book for screenwriting; Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting.

As the book’s name indicates, Field discussed the basics of screenwriting; in his opinion, every screenplay should have three parts, as Aristotle said. He called this the Three-act structure and explained the content of each part:

- Beginning or Act I: is the setting of the story and includes the inciting event, which sets the story to go.

- Middle or Act II: is the confrontation, where the protagonist confronts the inciting event and its consequences. The confrontation varies, depending on the type of inciting event.

- End or Act III: is the resolution. This act includes the climax of the story and the story ends.

Although Syd Field’s book is about writing screenplays, it became the bible for any type of storytelling. Not only most screenplays but also most novels are written in the three-act structure. If you don’t have time to read the entire book, I suggest reading at least its first chapter. It is a short chapter, only 15 pages. But it sheds light on the meaning of structure and clears up many misunderstandings.

Narrative Structure in Picture Book

In the realm of picture book writing, someone interpreted the three-act structure as “setting, problem, three trial-fails and solution” which you may have heard as “traditional structure”. My research to find out when and why this name got coined led to no result.

Regardless of why this interpretation of the three-act structure prevailed, this interpretation has a big problem: it oversimplified the meaning of “confrontation”. Confrontation is individual and unique to each story and to the traits of the protagonist. It is NOT necessarily trying to overcome an obstacle (three times!). A confrontation may be facing an unpleasant feeling and the protagonist learns to deal with that feeling at the end of the story. A confrontation may be facing a wrong belief in the society where the protagonist lives, etc. In a nutshell, confrontation cannot boil down to a formula, let alone giving a number of fails.

Apart from the limited interpretation, the naming is also vague. Why traditional? To differentiate it from what! From a modern structure? If so, what is the other one?! Based on this vague term, many more vaguer terms coined and prevailed; non-traditional structure, rule breaker, … which we will look at them shortly.

Before that, I quote two paragraphs from Syd Field’s book that were very useful for me.

One of the misconceptions about structure is that having structure means following formulas and killing creativity. Syd Field explains that structure is a paradigm and paradigm is a form. Then, with a very subtle example, he shows the difference between a form and a formula:

Wrong terms about structure

Why does it matter to recognize the wrong terms? If you are mistaken about what is not the structure with what the structure is, you cannot construct your manuscript. How can you possibly aim at a target while you don’t know it? You will see the importance of understanding the correct structures in the following analysis:

- Circular Ending, not circular structure: If the beginning and end of the story resemble each other, the ending is called a circular ending— the story circles back to the scene/sentence it started. The circular ending is only one type of many types of narrative ending. Bad news: if a manuscript has a circular ending, it doesn’t mean it has a structure! Imagine a multistory building. Its roof may have a swimming pool or some solar cells or a little garden, etc. The skeleton frame of the building is one thing, the type of its roof is another thing. The same is about the narrative structure and the narrative ending.

- Fiction or non-Fiction; that is the question: One of the foremost ambiguities in finding narrative structure in books arises when the difference between fiction and non-fiction is ignored. When someone writes fiction, she cannot randomly toss scenes, characters, and dialogues into the manuscript; a narration (story) needs a narrative structure. The same is valid for non-fiction. A non-fiction manuscript needs a structure to convey its concepts to the reader. Imagine an article in a newspaper about the change in the price of houses in a town over the last decade. It cannot have a narrative structure because it’s not a story. But, it should have a structure. The journalist cannot thrust numbers, facts, predictions with no order into the article. She should write her article with a text structure.

- Most of the vague terms about the structure are coined when the poor non-fiction book (or manuscript) doesn’t fit in any narrative structure simply because narrative structure is not applicable. So, the person coins a new name for the structure! If a book (manuscript) doesn’t have literary elements or narrative elements, it is not narration/fiction. Narrative elements are character, conflict, narrative structure, setting, point of view (POV9, etc. Narrative elements are MUST-TO-HAVE for a narration. They draw the line in the sand between narration and other types of prose and texts.

- It seems obvious, doesn’t it? But by looking at many self-coined terms about the structure among picture book writers, we see this basic definition has been a big pitfall for many; they simply confuse the narrative structure with the text structure. For example, profile structure is coined for books like Fry Bread: A Native American Family story (2019) by Kevin Noble Millard or We Are Still Here! (2021) by Traci Sorell. I guess because these books have “We” in many of their sentences, and some writers got confused with this “we” with the narrator in the story. Whereas both books are non-fiction; they have no narrative structure, character arc and POV. In another post, I will discuss their text structure.

- The story-within-story device, not the Story-within-story structure: Story-within-story (or framing story) is a sophisticated literary device. It’s when one of the characters tells another story. The greatest example of this device is One Thousand and One Nights. Bad news Adding a story in the middle of a manuscript does NOT give it narrative structure. It is important to know that story should have a strong narrative structure before another story adds to it.

- If you are wondering a picture book is too short to use this literary device, your answer is it is possible. In another post, we will go through the literary devices and on-page \ look at some examples of the story-within-story in picture books.

- Events’ order, not episodic structure, not linear structure: In storytelling, a writer may start telling the story from the end; remember movies that the protagonist, in his deathbed, remembers his youth and tells his life story. The writer is NOT obliged to follow the chronology of the events; she may tell some episodes of the protagonist’s life or may start in the middle. Or, even after the protagonist’s death and flashback. All options are available on the table for the writer. Mostly we see linear narration because the human brain understands causality easier. However, it’s not a rule.

- Having these options, however, does not mean that the writer does NOT need to understand the structure. First, she should identify the plot points in the structure; the beginning, the middle and the end. Second, choose how to order these plot points in her manuscript. Her choice of the order does NOT mean that the manuscript has structure.

- Genre is NOT a structure. Have you seen meta-fiction structure or mystery structure? Both are wrong terms and are the result of NOT understanding the meaning of genre.

- Parallel stories, not parallel structure: In a book with parallel stories, the writer tells two or more separate narratives. These stories should be connected with one theme or with an event or a common character. The parallel story is NOT a structure. On contrary, each of the stories should have its own strong and separate narrative structure. The difficulty of writing parallel stories is that the reader should understand vividly why the writer decided to have more than one story in the book. It is an achievement for a writer when the reader closes her parallel stories book with satisfaction, not confusion. If the reader reads to the end, though. Keeping the reader engaged in a book with parallel stories is a challenge.

- Cumulative Tale, not cumulative structure: I searched a lot to find out the difference between a story and a tale. If you know the difference, please let me know in the comments. Leave that difference aside, cumulative tales are only one type of tale and are not a narrative structure.

If you are interested to know about other (and correct) types of narrative structure, this reedsy blog post is a great start point.

In my previous posts, I looked at two important points in the beginning (Act I): the hook and the inciting event. We will continue with Act I and Act II and their important plot points in the next post. I am looking forward to reading your comments and thoughts.

This was such a great read and very informative!

How do you define “mirror” structure, or is it more accurate to say mirror story? In either case, how do you define it? TIA

Thanks for asking this question. I had not heard of this term and am not sure what exactly do you mean by “mirror structure”! I have two guesses?

1) You refer to “Foil Scene”. For example, at the beginning of the movie we see a scene in which the Protagonist is silent in school and unable to speak up. At the end of the movie, we see the same situation and characters, etc. But the Protagonist is able to speak up and defend himself. These two are foil scenes. They show a direct contrast, while the setting is the same.

2) You refer to “Paired Plot Points”. For example when Plot Point I (at the end of Act I) is paired with Plot Point II (at the end of Act II). Some people named it “Chiastic Story Structure”. However, it is not a different structure than the 3-Act structure.

These were my guesses. Could you, please, explain more or give an example of a book or a movie which people called mirror structure?